Logan Paul and the Myth of Cancel Culture

July 9, 2018This article originally appeared on VICE Canada.

There exists a popular and inarguably comical expression on social media—primarily Twitter, of course—known as “canceling.” Cancel culture is a makeshift digital contract wherein people loosely agree not to support a person (especially economically) in order to somehow deprive them of their livelihood. Some examples of canceled people and things: Kevin Spacey, Roseanne Barr, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, the Grammys, espresso machines, lip fillers, Kanye West. And as of 2017, when he brazenly published a video of a man who appeared to have died by suicide, many assumed millionaire YouTuber Logan Paul to be canceled, too.

But still, like the most stubborn of blemishes, he remains. Over the weekend, after a short two-week hiatus, Paul announced some news: He’s filming a documentary focusing on the toll his figurative cancellation had on his psyche.

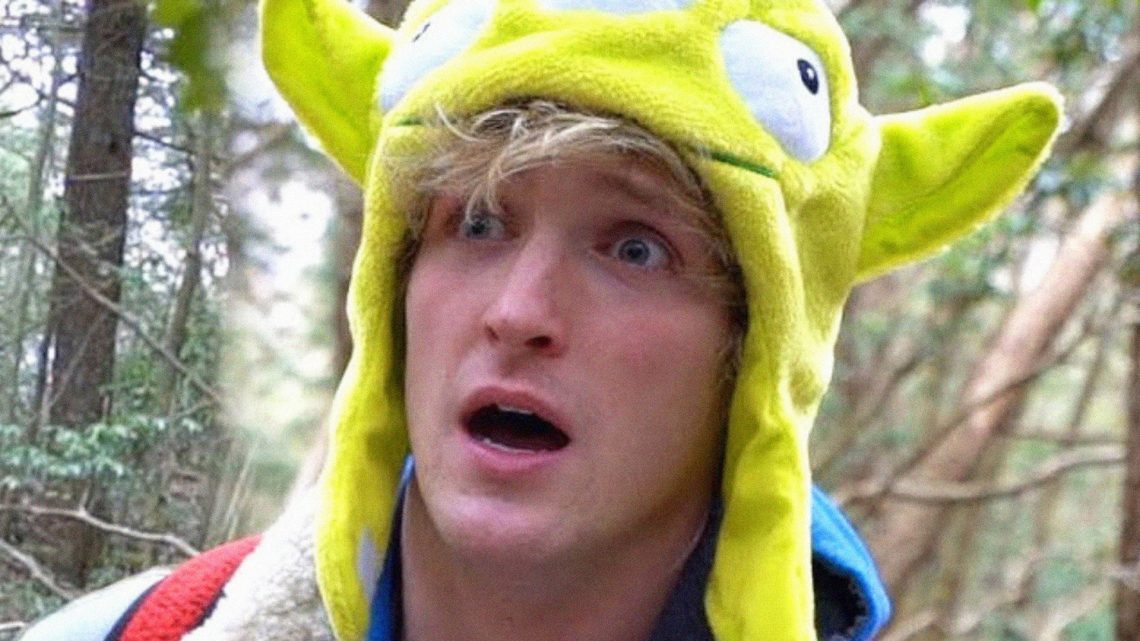

In late 2017, the 22-year-old social media star visited Aokigahara, a dense, treacherous forest on the northwestern flank of Mount Fuji, in Japan. The forest is a sacred site with a haunting reputation in Japanese mythology as the home of ghosts—and it is also among the world’s most prevalent sites for suicide. In a 15-minute vlog, which Paul published to his channel on December 31, 2017, then removed on January 1, 2018, he and his friends stumble across a corpse in the woods. The man’s face is blurred; the camera pans and zooms across his lifeless body. “Yo, are you alive?” Paul shouts, stifling laughter.

After a torrent of recrimination, Paul ventured to apologize twice: once, using the stock iPhone Notes app, then again, via a monetized YouTube video. “I’ve made a severe and continuous lapse in my judgment, and I don’t expect to be forgiven,” Paul said. “I’m simply here to apologize.”

Upon the release of the video and YouTube’s decision to yank premium advertisers from his channel, the internet swiftly threw a #LoganPaulIsOverParty—an ever-changing hashtag under which people metaphorically gather to celebrate the end of a person’s career. Naturally, though, Paul’s career wasn’t over. He continued making videos. He continued making millions.

The most obvious problem with cancel culture is that it rarely has any tangible or meaningful effect on the lives and comfortability of the canceled.

The expansive notion of cancellation is often more hopeful than it is plausible; as a democratic aspiration, it’s an exertion of agency and control, a reclamation of power. To withdraw from supporting someone whose actions and behaviors are now inconsistent with one’s values can feel like a radical boycott. Yet to succeed in the midst of cancellation is less of an exception to the rule than it is the rule itself. “Half the people that are listening to [my] album are supposed to not listen to the album right now. I’m canceled,” Kanye West recently told the New York Times, after telling TMZ that slavery was a choice. “I’m canceled. I’m canceled because I didn’t cancel Trump.”

The fever dream of cancel culture is that it is some centralized infrastructure of accountability. Since cancellation takes place online, it often stays there, usually only briefly: Spotify tried to boycott rapper XXXTentacion, then reconsidered. To legitimately cancel a celebrity (and prospectively remove their presence from wherever they thrive) would require actual intervention on the part of those supporting the individual’s platform. When YouTube temporarily suspended ad revenue on Logan Paul’s account, following the publishing of his December video, it didn’t affect his bottom line—Paul still made money from sponsored social media posts and merchandise, and his briefly monetized apology video quickly garnered 40 million views, which, potentially, could have yielded about $20,000.

“We can’t just be pulling people off our platform,” Susan Wojciciki, YouTube’s CEO, said at the Code Media conference earlier this year. “What you think is tasteless is not necessarily what someone else would think is tasteless.”

In the court of public opinion, celebrities regularly suffer challenges from the jury. But even holding a person accountable is dependent on a fixed hierarchy, a variety of measurable criteria: the prominence of the person, their popularity, their gender, and the quality of their apology. Cancel culture, to me, seems like a deeply personal journey rather than a sweeping, universal one. It’s a plebiscite, not an official ruling, in which the terms and conditions are often hazy.

The public’s rare, unequivocal rejection of a problematic celebrity often hinges on the severity of their offense. In the cases of major abusers in Hollywood—Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein—it is increasingly obvious that their futures have been reduced to ash. But when it comes to other indefensible people—Louis CK, Kevin Spacey, Roseanne Barr—the terms of their cancellation seem less permanent. It’s quite possible that they’ll continue on with their careers, suffering little more than a short monetary drought.

The sooner we stop pretending cancel culture is a binding, comprehensive movement rather than an individual decision, the easier it might be to come to terms with the fact that gravity has a delayed (and sometimes nullified) effect on people like Logan Paul. YouTube, and often, the internet, reward drama and sensationalization. And as Robinson Meyer writes for The Atlantic, “The internet's only currency is attention.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Connor Garel on Twitter.