The First Movie to Tackle the AIDS Crisis Is a Buried Treasure

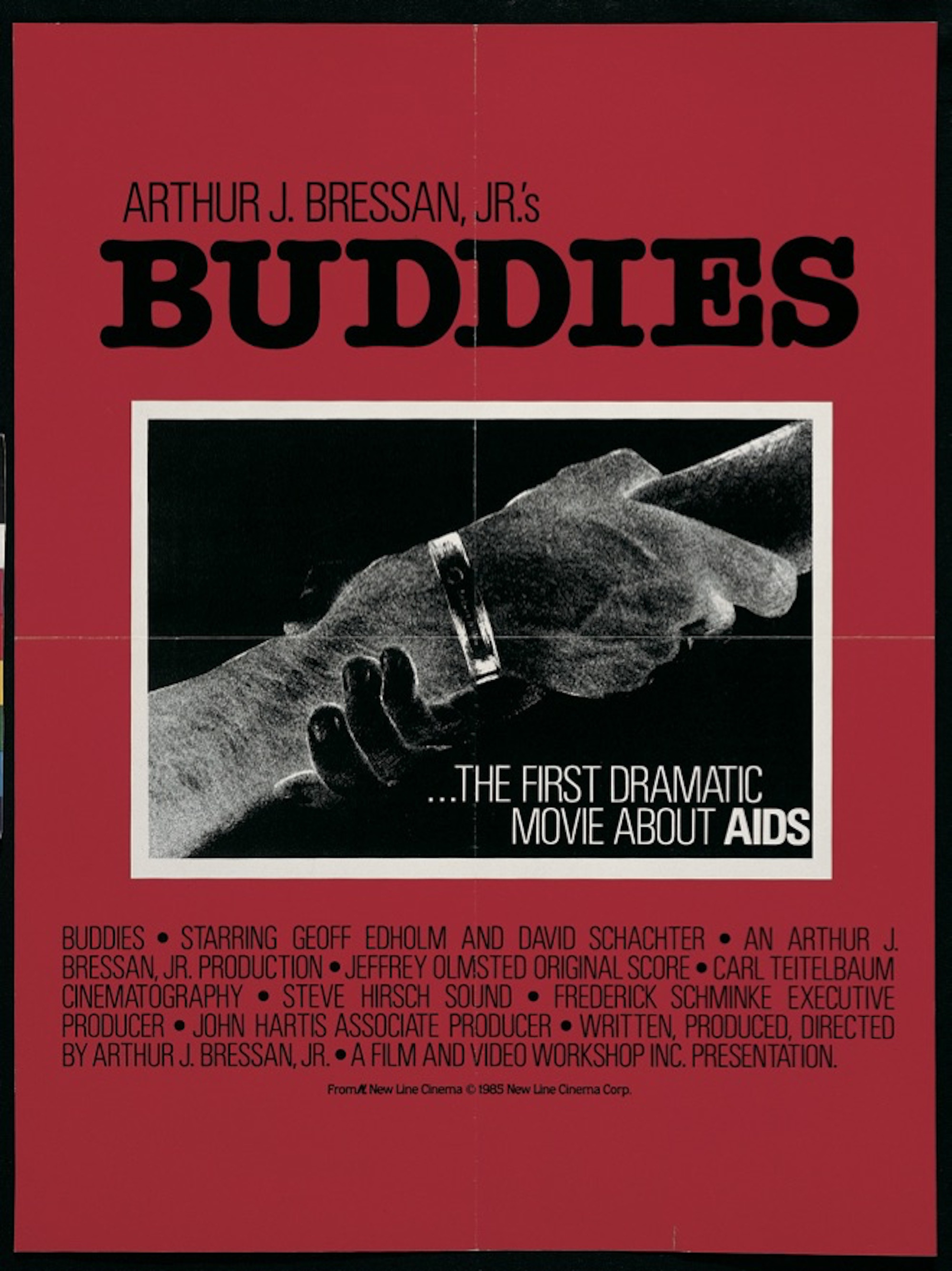

June 22, 2018Five days after the 1985 premiere of Buddies at the San Francisco International LGBTQ Film Festival, President Ronald Reagan made his first public mention of AIDS. Although it was unrelated to the American underground filmmaker Arthur Bressan, Jr.’s final masterstroke, the timing was not coincidental: 5,636 AIDS-related deaths were reported that year, including that of Reagan family friend Rock Hudson. In 1985, the AIDS crisis had reached a breaking point and Buddies was the first-ever feature film to address it.

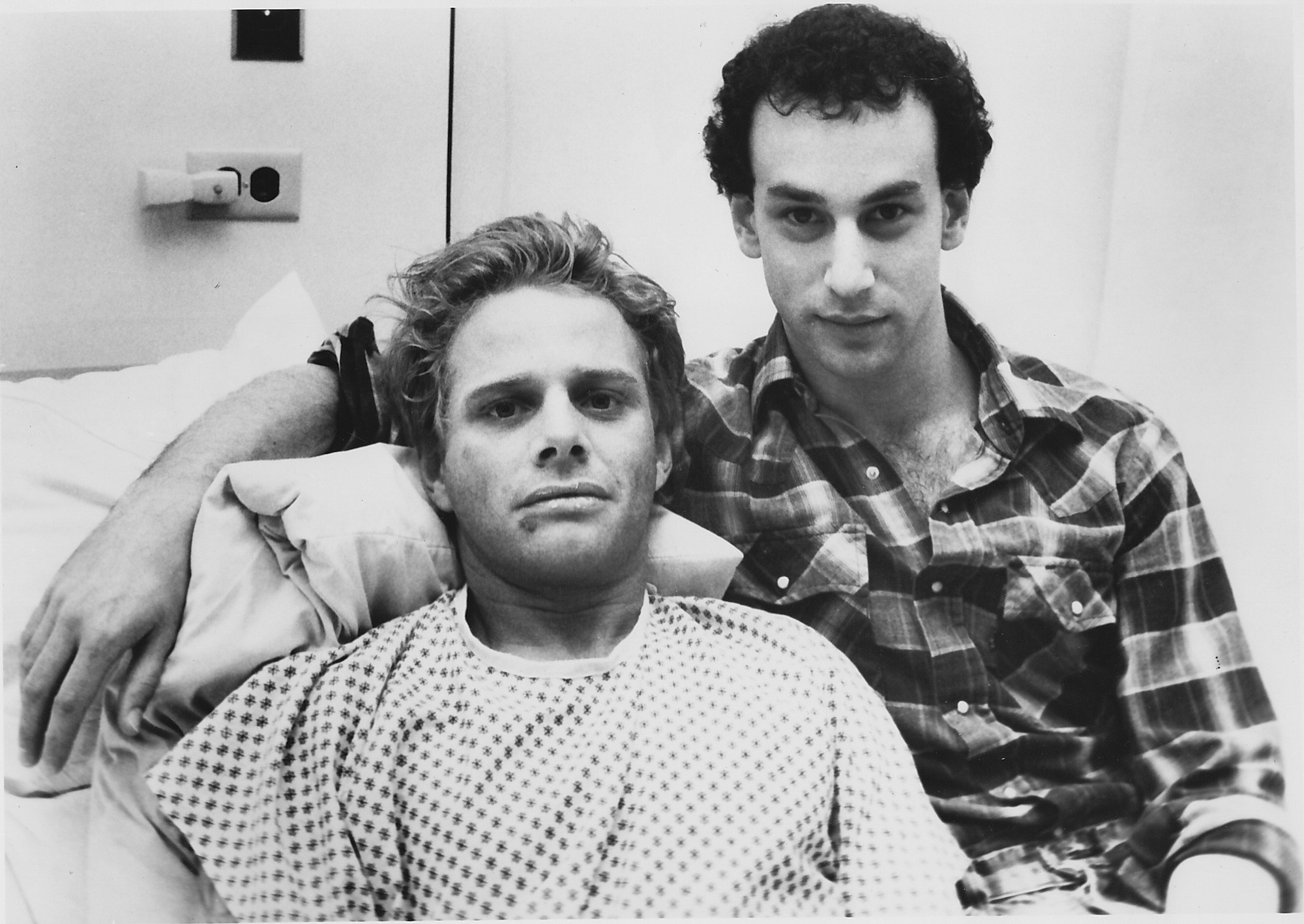

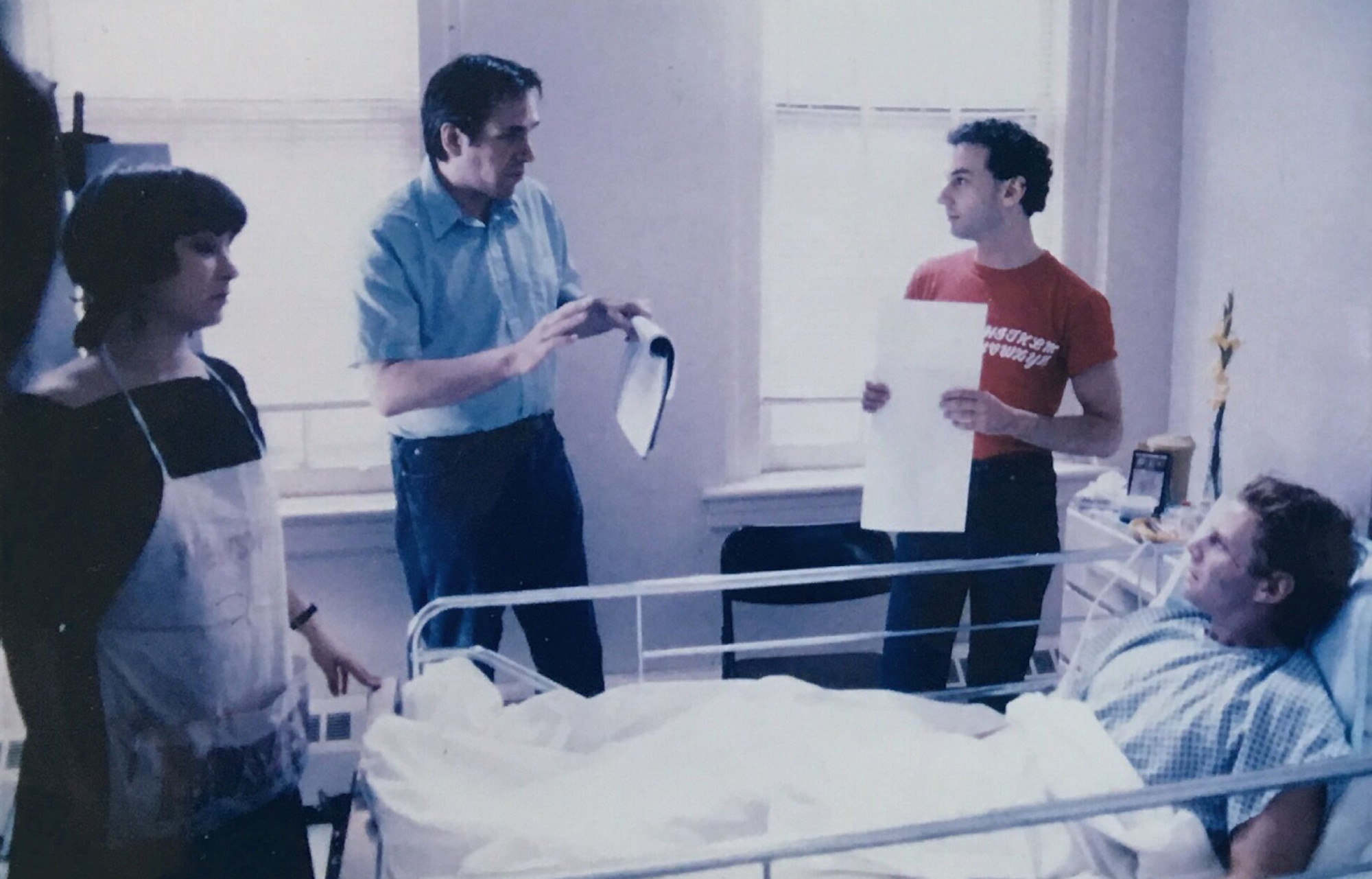

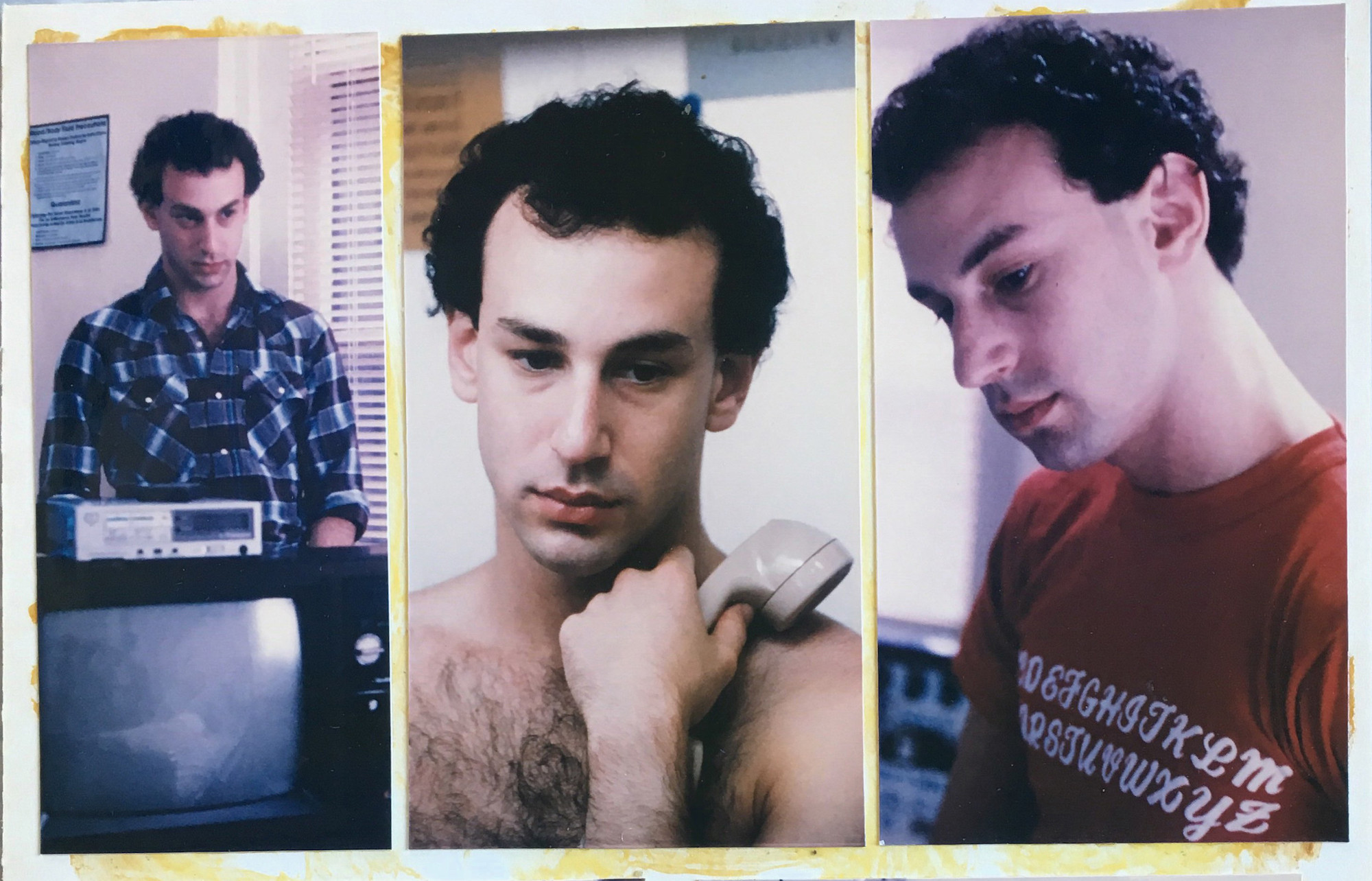

Written in five days and filmed in nine, Buddies tells the story of David (David Schachter), a gay typesetter who volunteers at the hospital as a companion to the dying Robert (Geoff Edholm). No other characters appear on-screen for the entirety of the 81-minute film. Created on a shoestring budget of approximately $27,000, Buddies was at once a formally experimental two-character play, a heartbreaking cry for visibility for those afflicted, and a touchstone in the history of LGBTQ+ film.

On June 22, thanks to the efforts of the Bressan Project, film historian Jenni Olson, restorers Vinegar Syndrome, and Frameline Distribution, the film will begin a weeklong run at The Quad cinema in New York. Ahead of this landmark revival, I interviewed Olson and Vinegar Syndrome co-founder Joe Rubin about the late Arthur Bressan, Jr., how Buddies disappeared, and what it means to breathe new life into this urgent and beautiful film.

VICE: What’s the story behind Buddies becoming a film?

Jenni Olson: Arthur saw the early days of AIDS and the stories unfolding throughout the community as the most important political story of its time. The simple unfolding of the relationship between a dying gay activist and his until-now apolitical gay buddy serves as the perfect conceit for a very Capraesque tale. We see how one passionate individual can maintain his vision for justice—and through a deceptively simple unfolding of the story, the filmmaker completely captures the heart of the audience and enlists us in this struggle as well. Bressan was very influenced by Capra and even interviewed the great Hollywood director back in the early 70s for Interview magazine.

Despite Philadelphia’s attempts to claim the prize, Buddies was the very first narrative drama about AIDS. At the end of his life, Arthur was interviewed by his dear friend, film historian Vito Russo, for the second edition of Russo’s book, The Celluloid Closet. Arthur said of Buddies: “Every once in awhile you get the chance to make a statement on film that has nothing to do with your career, with ego, with money—but only with the issues of life and love and death. If Buddies is my last film, it’ll be a fine way to go."

Joe Rubin: He was, to a certain extent, hoping that the film would force the issue, but also basically trying to make a film which humanized people who had [AIDS]. Obviously, at the time it was made, which was 1985, the disease still had a lot of stigma associated with it. It was made and released at a time when a vast majority of the world, but definitely the American public, had a lot of misconceptions about what the disease was and a lot of confusion and uncertainty. The film was both constructed as a way to force people to think about it, but also to humanize people who had it.

How did you get a hold of Buddies?

About ten years ago, I finally found a copy. Years later, when I was actually doing distribution, one of the first library acquisitions that one of my colleagues made was a company that had at one point in the late 80s briefly handled Buddies theatrically.

So in this library acquisition we ended up with the negative for Buddies, but we had no rights to it. Eventually, I was either put in touch or was reached out to by Jenni Olson, who is the current spearhead of a lot of what’s going on with the film and some of Arthur’s other films. She was just a big fan of his work, and in particular Buddies. She basically took it upon herself to track down his sister because Arthur died of AIDS as well. As such, his estate and his work was in copyright limbo because he wasn’t there to represent it. He had no direct heirs except for his sister, and she basically proved very difficult to find, so Jenni eventually tracked her down. She was pleasantly surprised that there was an interest in his films and we basically worked out a distribution deal where we’re handling the home video and some of the broadcasts, and then Frameline Distribution is handling the theatrical as well as the visual.

How does it relate to similar-minded films of the era?

Olson: Before the arrival of the New Queer Cinema of the early 1990s, Film Comment proclaimed the mid-1980s as the era of the Gay New Wave. This major Film Comment overview came out in 1987, well after the release of Buddies and mainly in reference to the almost simultaneous theatrical releases of a quartet of gay indie films: Desert Hearts, Parting Glances, Dona Herlinda and Her Sons, and My Beautiful Laundrette.

Buddies can definitely be seen as an immediate precursor to that wave in those early years of the 80s when gay films were so rare. My old friend Mark Finch, who ran the San Francisco Lesbian & Gay Film Festival with me in the early 90s, used to characterize that earlier time by saying, “Remember when there was only one gay film a year and it was always from Europe?"

As the 1980s wrapped up we started to see the wider release of bigger LGBT films. Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy was notable for being released in multiplex theaters when previously most gay films were only being seen on arthouse screens.

How was the film received when it first came out?

Rubin: That’s sort of a tough question because the film barely had a release. Initially, he produced it by himself and the film was shot in May of 1985. It had its world premiere in September 1985—so about four months of production and post-production, which is a very quick turnaround for a feature. When the film initially was screening, it was basically making a very small festival run, and an unfortunate consequence of the subject matter was that it didn’t really get much initial exposure outside of gay film festivals, which is unfortunate because even though the central characters are supposed to be gay, the film really isn’t entirely focused on that. It’s kind of evident in the final sequence, in which David is walking with his protest sign that says, "AIDS is not a gay issue." That’s part of the point the film is trying to hammer in—that this is not an issue that only affects a certain part of the population. As a consequence of the gay film festival screening environment, the audience was very specified. It was an audience that already agreed with a lot of the ideas that were presented, or at least had more grounding in them. So it didn’t have the effect that he was hoping it would have, which was basically exposing people on a wider scale. When New Line picked it up [in 1985], it got a little bit more mainstream distribution—it played at art houses. It did a small run, but it really wasn’t released beyond that. The film was basically impossible to see from around the late 80s through now.

Why is it important it gets revived today?

The context under which the film was made basically forces it to be a landmark in film history, and I think that is definitely worthy of revisiting. On a more personal level, I like films that come from the mind of directors who are very consciously unconcerned with commercial viability, because they tend to be a more earnest, sincere reflection of what mattered to them artistically, socially, aesthetically, etc. Bressan is a really interesting filmmaker. He was able to make movies that probably made a certain amount of his audiences uncomfortable, and that’s always good, and also presented viewpoints that, within cinema—especially of the time—really didn’t exist. He was technically competent. He was good with creating interesting characters and working with actors, and he knew how to make the most of low budgets and limited resources.

Olson: I really love the idea of Buddies as a kind of time-capsule message from the gays of 1985 to the gays of 2018. I hope that LGBT audiences today will watch the film and vividly feel the importance of being politically engaged in the social issues of our time. We are at a very different juncture in terms of HIV/AIDS, but obviously HIV/AIDS remains an issue that has disproportionate resonance for our community. And there are so many other issues we face—and Buddies serves as a truly inspiring tale from which we all can learn.

Click here to get tickets for Buddies.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Emerson Rosenthal on Instagram.